“That which is measured improves. That which is measured and reported improves exponentially.” – Karl Pearson

As modern humans we love to measure things. We measure so that we know how well we are doing, and to compare our performance to others or to some ideal scenario. Innovative hardware (coupled with software and connectivity) such as wearables, phones, and even home exercise equipment have made it easier to measure, store, and compare all sorts of personal data.

One of the core principles driving the last fifty years of business has been finding the “right” metric(s) by which to track a business and then ideally tying incentive compensation (particularly for executives) to the achievement of this metric.

In my CFO roles (both full-time and fractional) a topic that often arises alongside annual planning is, “What metric(s) should we track?” Leadership teams wonder what metrics to present to all employees (and report against regularly) which will neatly reflect the strategic priorities for the year. Board members and prospective investors ask executives to present the primary metric or metrics they track. As these are usually outputs, investors often want the so the key performance indicators (inputs) tracked that in combination results in the output metric being optimized.

Is Simpler Better?

“Simpler explanations are generally better than more complex ones.” – Distillation of Ockham’s Razor

Simplicity is a much-loved virtue in business today. Entrepreneurs looking to raise money are advised to be able to tell the story of their business in a few sentences or less than 30 seconds.

When it comes to metrics, the common advice is for CEOs to pick and companies to focus on and track a single metric.

The positives of having one metric or goal to focus on are as follows:

- A single goal leads to focus and thus efficiency.

- A single goal leads to clarity and thus greater alignment across teams.

- A single goal offers a framework for decision-making leading to fewer disagreements between groups or executives.

- A single goal presents an easy way to solve problems. When disagreements arise, they are adjudicated primarily based on which solution contributes most to improving the primary metric.

The Most Commonly Tracked Single Metric: Growth Rate

Paul Graham (co-founder of Y Combinator) described a start-up in his 2012 essay as “a company designed to grow fast.” Start-ups that join Y Combinator measure growth per week – the best measure of growth being revenue and the second best being active users. The YC goal is 7% growth per week, which over the course of the year implies a company grows its revenue (or active user base) by 34x.

Those who have spent any time talking with venture investors (whether in a Board room or a pitch meeting) know how focused they are on revenue (or bookings) growth rates.

The reason for this singular focus is the correlation between growth rates and valuation multiples. High valuation multiples allow investors to earn a handsome return on their investment.

Here’s an example we saw in recent years…

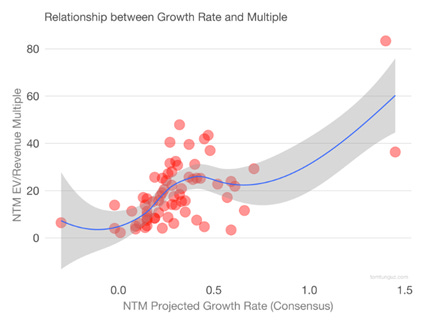

Since the market low in late March 2020 through January 29, 2021, the S&P 500 was up 69% by February 2021, the NASDAQ composite was up 91% and the WCLD (a cloud computing ETF) was up 148%. In an effort to explain the run-up in stock prices and expansion in multiples, Tom Tunguz wrote a post called “The Missing Insight Around Software Multiples for Valuing Companies.” The piece contains the graph below showing the geometric curve of forward multiple of revenue in relation to growth rate, reflecting the power of compounding that Paul Graham refers to in his essay when talking about the importance of high weekly growth rates.

Clouded Judgement, a Substack blog, posts valuation data and trends on cloud/SaaS public companies. A regression (shown below) of similar data as used by Tom Tunguz shows a R2 of 0.45. While the validity of R2 as a good metric is widely debated, it does indicate that there are other factors beyond growth rate which influence the revenue multiple and valuation.

Revenue growth is thus not the only variable that matters and hence probably should not be the only metric tracked.

The North Star Metric: A Better Single Metric?

In my piece on the annual planning process, I advised CEOs to speak about their North Star metric with the Leadership Team before any actual spreadsheet work commences.

The North Star metric, defined by Sean Ellis who is also known for coining the term Growth Hacking, is meant to represent a single metric that is most predictive of a company’s long-term success. More specifically, it is meant to be a metric that captures how customers get value from the company’s product.

Quite often customer value has to be ascertained through tracking a proxy metric, typically product engagement or usage. The North Star metric is nights booked for Airbnb, daily active users for Facebook, messages sent for WhatsApp, weekly rides for Uber, and time spent listening for Spotify.

The logic of using a product metric is that if customers are engaged with the product that should reasonably imply that they are receiving value from the product. And, if customers are getting value they will continue to pay (i.e., not churn), possibly buy additional services, or repeat purchase, and recommend the product to others. In the case of advertising supported services (FB and the Spotify free tier), higher usage means the audience will be exposed to more advertising placements which drives revenue.

High Engagement Does Not Always Mean Value Is Being Realized

The examples of a North Star metric given above are all in businesses selling primarily to consumers. In B2C businesses, engagement is more tightly correlated with value than in B2B businesses. Consumers are both the “buyer” and the “user”, and thus will not continue to pay for something they find of low value.

Business users may not have made the final purchase decision. In case, those who must use a product on a regular basis may not be pleased with its ease of use or performance. They would look for alternatives if the switching costs were manageable, and there weren’t the sunk costs of onboarding and a long-term contract. Users of most ERP systems and of Salesforce would attest to this fact.

Put another way engagement metrics (and most financial metrics, especially revenue) are “quantity metrics.” Jonathan Golden, an NEA VC and former Airbnb executive, talks about the difference in the types of metrics in an HBR article. In quantity metrics, more is always better. Quantity and quality sometimes go hand in hand, but not always, so high engagement can also be a result of a poorly designed product.

The Negatives of Adopting A Single Metric as the Company’s Focus

As you can probably tell by this point, I am not a believer in a single metric. In my experience, the negatives associated with reliance on a single metric outweigh the positives.

These are the negatives I see:

- Tunnel Vision and Goodhardt’s Law. Focusing on one metric at all costs can lead to unintended consequences. The power of incentives is well known. When incentives (monetary or reputational) are tied to one outcome, a common occurrence is gaming the system to create an increase in the desired outcome at the cost of other things, which though not obvious can be harmful to the business in the long term. Goodhart’s Law is generalized as, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

- Miss early warning signs of strains on the business. A sole focus on quantity metrics can lead to missing weakness in quality metrics such as employee happiness and morale or weakening customer support metrics. It’s hard to forecast when the weakness in a quality metric will lead to a negative tipping point in the quantity metric. When that feedback loop, in this case a vicious cycle, does occur is hard to forecast. Just know it will. Morgan Housel published a compelling piece on how feedback loops are hard to predict and can have exponential (positive or negative) impacts.

- A false sense of security. Growth is strong so business must be doing well. However, for all business profitability (both at the unit level and the company level) matter. Profitability is an efficiency metric. Businesses can and do fail or struggle when growth is strong, and efficiency is poor. Some notable examples include Homejoy, WeWork and Blue Apron.

- People will feel left out. As much as we may try to find a linkage, not everyone’s day-to-day job can be clearly linked to “the single metric.” If only one metric is talked about at All Hands meetings, those whose jobs don’t directly influence this metric may feel unimportant to the business and thus lose their motivation.

- Harder to innovate and focus on the long-term. As the competitive playing field changes, companies need to adjust and refine their strategies. Having a single metric reduces the likelihood of innovation or trying new things until a new single metric is chosen. Most single metrics are focused on the short to medium term. Building and launching a new product or entering a new geography which will reach scale in 12-18 months from now may well be critical to long term success but will not drive the single metric upwards in the next quarter or two. If things get tough in the core business, there will be a lot of pressure to take resources away from the longer-term project (only temporarily, executives will promise.) And that will sap investment to drive long-term growth.

- Hard to change old habits. As much as we may want to be different from our parents, as we age, we all learn that it’s hard to change. This applies to employees in companies too. When the corporate focus is on one metric and the CEO decides to change that metric, it’s hard to get employees to change. Often the behavior that drive that single metric has become part of the culture. Changing an established culture is really, really challenging.

So, Then What? Adopt multiple metrics that reflect the needs of all stakeholders.

In every organization, there are three stakeholders. The needs of all three must be met to have a successful business over the long term. These three stakeholders are: (i) investors, (ii) customers, and (iii) employees.

Here are some suggested metrics that are reflective of the primary interests of each stakeholder group.

Investors – Investors are seeking both growth and efficiency. Metrics that combine these two would include.

- Rule of 40

- Return on Invested Capital

- Unit Economics

- LTV to CAC Ratio

These are all financial metrics. Financial metrics are lagging indicators and thus while efficiency is important, I recommend not relying solely on a financial metric to gauge if a company will continue to perform well.

Customers – Customer are not interested in the growth or financial success of a business. They simply want a high-quality experience at every business interaction. Metrics that are reflective of quality as experienced by the customer include.

- Some version of a customer satisfaction score such as NPS or CSAT.

- Net Dollar Revenue Retention.

- SaaS Quick Ratio

Employees – Employees care about quality of their workplace experience (including work environment, company culture, strength of their manager) and efficiency (can the company afford to promote and pay me more as well as bring in another needed resource on my team).

- An employee engagement score

- Willingness of employee to recommend the company to friends as a great place to work.

Simplicity is Overrated.

“Make things as simple as they need to be, but no simpler.” – Einstein

Focusing on only one metric makes things too simple. And that simplicity has a cost. Singular focus on one metric reduces independent thinking. It becomes harder to disagree, debate or raise red flags when a single metric is used to judge success. The metric becomes an end rather than a checkpoint along the journey.

Businesses are complex things, much like living organisms. Yet most humans dislike complexity. Complexity makes it harder for people to sell a single formula for success. Complexity requires making trade-offs. Trade-offs require judgment.

A single metric is the business equivalent of black and white thinking. We all know how black and white thinking can lead us astray in our personal lives and relationships. The same is true in business.