What does it take to become the leader you’ve always wanted to work for?

“If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more and become more, you are a leader.” — John Quincy Adams

“Management is the opportunity to help people become better people. Practiced that way, it’s a magnificent profession.” — Clayton Christenson

Companies want to hire or promote into leadership those with the potential to be great managers.

Employer Question: “Will this person be able to recruit, motivate, develop and retain a high-performing team?”

Employees, when evaluating new companies and new roles, agree that the quality of their manager is a critical factor in their selection process. Typically, at the top; if not in the top three.

Prospective Employee Question: “Will I enjoy working with and grow through the relationship with my manager?”

Everyone seems aligned on the preferred outcome. Yet employees often complain about the quality of their manager and reminisce about their one great boss (from the past). Companies find it challenging to hire great managers.

I have a few hypotheses to explain the existence of this gap when the desired outcomes are so well agreed. And some suggestions on how to approach being a better manager differently than the conventional wisdom.

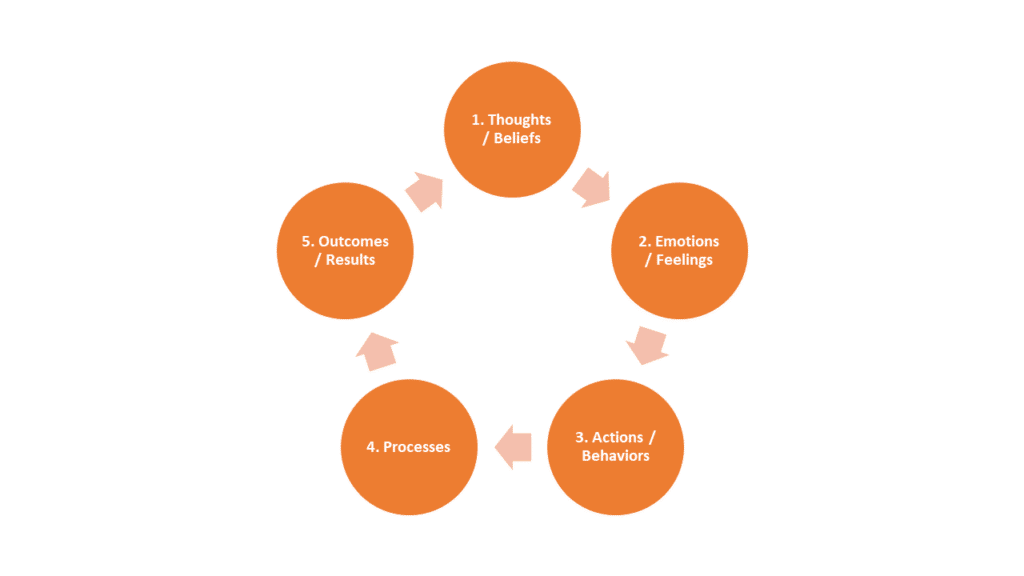

Borrowing from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, here is my slightly modified version of that rubric applied to management – both the evaluation of potential managers and the tool kit to use yourself.

Why The Gap?

First, being a good manager is really hard. It is much harder than being a good individual contributor. The challenge is management requires focus on the self and focus on others, at the same time in the appropriate measure. Individual contributors are only tasked with optimizing their own performance.

In the evaluation of leaders, the focus tends to be overwhelmingly on the numbers 3, 4 and 5 above. These markers are items which I believe are “necessary but not sufficient” in evaluating potential managers and/or predicting their impact on team morale, performance, growth, and retention.

- Survivorship Bias and the Natural Tendency to Think Backwards. We use results and outcomes (#5 above) to evaluate the skills of people as great leaders and managers. This is the “get shit done” mentality, which people will proudly talk about in interviews or their LinkedIn profile.

- While it is unlikely that terrible managers create strong results, results are an outcome rather than an input. Often, people are present when great results happen but are not individually a meaningful driver of such results. That can be due to working in companies with tremendous tailwinds (e.g., Peloton from mid-2020 onwards for about 15 months) or with huge moats which they did not create (e.g., being at AWS or Google Search currently.)

- Conflating Financial Success with Management Skills. The easiest to measure outcome is financial value creation. Those people who are in leadership roles at larger companies which experience financial success (i.e., stock price increases or unicorn/decacorn exits) during their tenure are most likely to be featured in articles, in videos, on television, or on social media. As those evaluating people, we are naturally drawn to those who are heavily featured in the media.

- Processes and Documentation Feel More Real. When asked to give examples of how leaders have driven team success, they will often point to processes put in place (e.g., new sales methodology, new product intake process etc.) or new documentation (e.g., incentive compensation plan redo, new order forms etc.) These are examples of tangible items which can be shared (even if in a digital form) with the prospective hiring manager or HR to prove effort in a leadership role.

- When things are working well, process documentation and checklist creation can help with scaling. Incentive compensation plan restructures can add fuel to an already burning fire. However, none of these documents or processes are likely to have created the initial success by themselves, nor will they help when the business environment is changing rapidly or when new surprises arise.

- Actions Seem Like the Appropriate, Controllable Inputs, but Often Aren’t. We are now able to measure tasks, events, and actions in many knowledge-based roles. Such as, how many calls are made, or e-mails are sent in a day by a sales rep. Or how many potential candidates are reached or interviewed are scheduled for each open role in a week. Or how many new pieces of content are posted in a week and how many views each item garners.

These all are items that can be reported in dashboards and shared with the Leadership Team and Board. Often these metrics, even when on plan and slowly improving over prior periods, don’t lead to financial result outperformance. (The reason for that merits a separate piece.) Regardless, measuring and tracking these sorts of controllable actions is not a good indicator of employee engagement or the morale of a team.

Invert The Problem. Focusing on the Unseen.

Management is about getting the best out of people on a consistent basis. Hence, I think the rubric from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is hugely valuable. A business after all is simply a collection of people working together towards common goals. Thus, understanding the beliefs and feelings of each person in the organization is hugely important in releasing their full potential.

Beliefs and emotions are “unseen” in the workplace because they are viewed as personal issues and less worthy of a manager’s time or attention. For those who delve into this area with their individual team members, I have heard of it referred to as “therapy,” which though well intentioned suggests an interaction beyond the normal bounds of a workplace relationship.

Most of my management “training” has been on the job rather than through formal courses or coaching. So, feel free to take what I have to say with a grain (or several) of salt. Here are some principles I have applied in my management approach, particularly as a new leader of an existing team. I hope these offerings might be helpful to you in enhancing your management skills and provide a roadmap you might ask potential employers in interviews when they are courting you.

Think From the Perspective of Employees. Channel Your Empathy and Compassion.

- Go Beyond the Obvious When Introducing Yourself.

- The Obvious. Introduce yourself by talking about your career path and work experiences. Use the experience to create a halo of competency around yourself. Talk about your vision for the group and use language that indicates and reinforces your authority.

- The Less Obvious. In addition to everything above, focus on the relationship you plan to build with your team. Present yourself as a full human, a person whom they can relate to (in some ways), a person who is willing to be vulnerable, a person who has made mistakes in their career, a person who has their own fears (about a new role). And most importantly, a person who cares about the team members as individual people.

- Understand, Empathize and Proactively Address their Fears and the Uncertainty.

- Sudden change of all types, and particularly the hiring of a new “manager,” creates uncertainty. As humans, we are wired to dislike uncertainty intensely. Become aware that your hiring as the new manager (from the outside) has created a lot of uncertainty for your team. Call it out openly. It is one of the hidden elephants in the room that gets less scary through exposure.

- The team members might be wondering (without saying it aloud): “Do I have to prove myself again?,” ‘’Will the new boss bring in their own people? Is my job at risk?,” “Will I be micromanaged?”, and “Is the new leader going to be fair?”

- Recognize the need to “Build” Trust. It must be Earned and not simply Expected.

- Recognize that building trust will take a while. Trust is hard to build and easy to destroy. Talk openly about your desire to build trust and the importance of trust (also referred to as ‘psychological safety’ in high performing teams.)

- Set high performance standards while normalizing and accepting mistakes, which happen at all levels.

- Set regular one-on-one meetings. Ensure you keep doing these meetings, even when it might be easy to skip them to give people back time. This personal connection is even more important during COVID with many folks remote. Let them know these meetings are their time (even if there is a templatized information sharing structure, which they can fill out.) Encourage them to talk about whatever is on their mind.

- Listen a lot. Ask open-ended questions from a place of curiosity. Encourage more description and context of any problems they are experiencing.

- Be Transparent. Narrow Information Asymmetry.

- As the leader of the team, you will have access to more information on the business, things happening in different departments, as well as overall company performance. Overshare with the team (unless the information is very, very sensitive.) It is commonly said that “information is power.” Share to empower your teams. Transparency builds trust.

- Focus on the Short Term and the Longer Term. The latter takes effort and is not commonly done.

- The short-term focus might involve quarterly goals for each team member. Ideally these are goals that roll up to department goals and then to company goals, so that people understand how their performance drives overall business success.

- Focusing on the longer term has two components. First, at least twice per year and even quarterly, spend time with your team members talking offsite about the professional ambitions (beyond this job and even this company.) Let them know you care and want to help them create a plan to achieve their objectives. Second, with your most senior direct reports, indicate to them that you would like them to grow and develop such that they merit your job. Create a plan for their growth. It is up to them to embrace the opportunity, but up to you to create the path.

Other Behaviors I Have Found Useful along my Management Journey to Become the Leader You’ve Always Wanted to Work For

- Be a Teacher.

- Part of the reason you have this senior role is that you have broader experiences than your team. Use the learnings from those experiences as arrows in your quiver to up level the whole team.

- Teaching for me has been about more than enhancing the functional expertise of my teams. I believe in teaching everyone the business model in depth, so that they understand how their roles and those of everyone else in the organization contribute to the overall goals and eventual success of the business.

- Seeing who embraces learning (and steps forward to take it in actively) will also tell you a lot about the long-term potential of your individual team members.

- Anticipate Problems.

- New leaders are often handed “hidden” problems that even the hiring team was not aware of and quite often does not disclose. Often these relate to compensation discrepancies within the organization or to the market in terms of pay, titles, and role descriptions.

- Spend time thinking about potential future problems that might arise (even from success). It is much easier to resolve problems when you can see them coming.

- Understand potential Career Paths for your Team Members.

- Remember that most employees are actively looking for the next jump in their career. At the very least, they want to know when it could happen.

- Remember that they will be getting a lot of inbound interest (over LinkedIn and through friends) for other roles that are being positioned as more senior, more exciting, and higher paid.

- Know what the “next promotion” would be for each team member, even if the opportunity does not exist (today) in your company.

- Be able to describe that role.

- Know what “Good / Better / Best” looks like for each role in your organization, so that you can both evaluate the team and give them guidance for growth.

- Lean on your People Team for help.

- Look for Strengths

- Everyone has strengths and weaknesses.

- Successful managers build on the strengths of their team members and find a way to manage around the individual weaknesses. Not every weakness can be overlooked, but one of the key skills in management is figuring out how to manage that weakness through assigning people to roles where they can excel and pairing them with others who have complementary skills.

- Seeing the strengths of people and talking about it proactively with them is a way to both increase motivation and get back good ideas about how to make things better in the business.

- Set Realistic Expectations.

- It is always better to under promise and overdeliver.

- When hiring new people onto your team, set expectations about the role and the career path before they say yes.

- Tell people early on if the career opportunity they want is either unavailable at your organization or at least unavailable for an extended period. Agree to be a resource to them (if deserved) when they decide what to do. In this way they are much less likely to leave you stranded.

The Hard Work is Worth It.

Being a good manager is hard work. You need to get your hands dirty – both by doing some of the work alongside your team and by talking through the hidden emotional issues (beliefs and feelings.)

Putting in this work will earn you loyalty from your team. That loyalty will make it easier to hire and retain people, will help you get the best out of them, and will mean they will want to work with you in the future at a different organization.

The hard work is worthwhile. You will see people flourish and find both greater success (promotions and pay increases) and satisfaction (happiness, engagement, and purpose) in their professional journey.

Join our community for more tips on leadership and business acumen. Learn more.